Published:

October 15, 2025

Author:

Justin Brodie-Kommit, PhD

My lifelong fascination with the natural world led me to the lab environment early in my undergraduate training at Bucknell University. I was drawn to Dr. Stowe’s research on cyanobacteria, where I spent four intense years diving into questions outside the sterile bounds of teaching labs. This commitment to primary research caught the research bug and led me directly to my PhD work at Johns Hopkins.

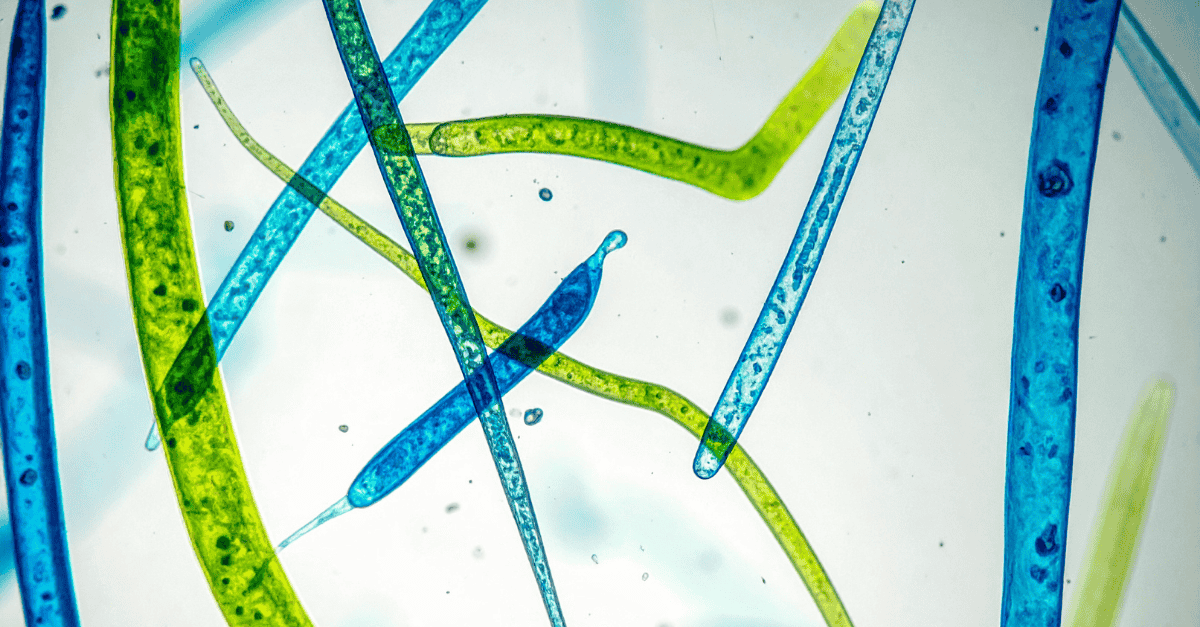

Our lab focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms that allow cyanobacteria to adapt their light-harvesting pigments—a survival strategy known as Complementary Chromatic Adaptation (CCA)—in response to changing light environments. My research on Gloeotrichia UTEX 583 revealed a critical lesson: our canonical understanding of the molecular responses to light did not hold across all closely related species. Life, it turned out, was more diverse and resilient than the textbooks suggested.

Conducting this research required fundamental, old-school molecular biology techniques. At the time, the genome of the species I was working with was not fully sequenced. We had to work harder, using methods like Southern blots, which were already antiquated. This forced me to appreciate the sheer scale of the biological frontier that was opening up. In the past two decades, the cost to sequence DNA has declined over 100,000X , finally providing large-scale access to the impressive 3.5 billion years of evolution that biology has been refining.

Today, my research career has come full circle with Lichen Ventures. The lichen organism is one of the most resilient structures on Earth precisely because it is a symbiosis between a fungus and cyanobacteria (or algae). It’s a living model of interdependence, survival, and adaptation.

Read the full paper here.

Motivated by a profound concern for vulnerable populations and ecosystems, Justin is committed to making a difference in the face of our climate crisis.